How can we redesign PETA's no-kill database so that users will want to use the tool and engage with PETA deeper?

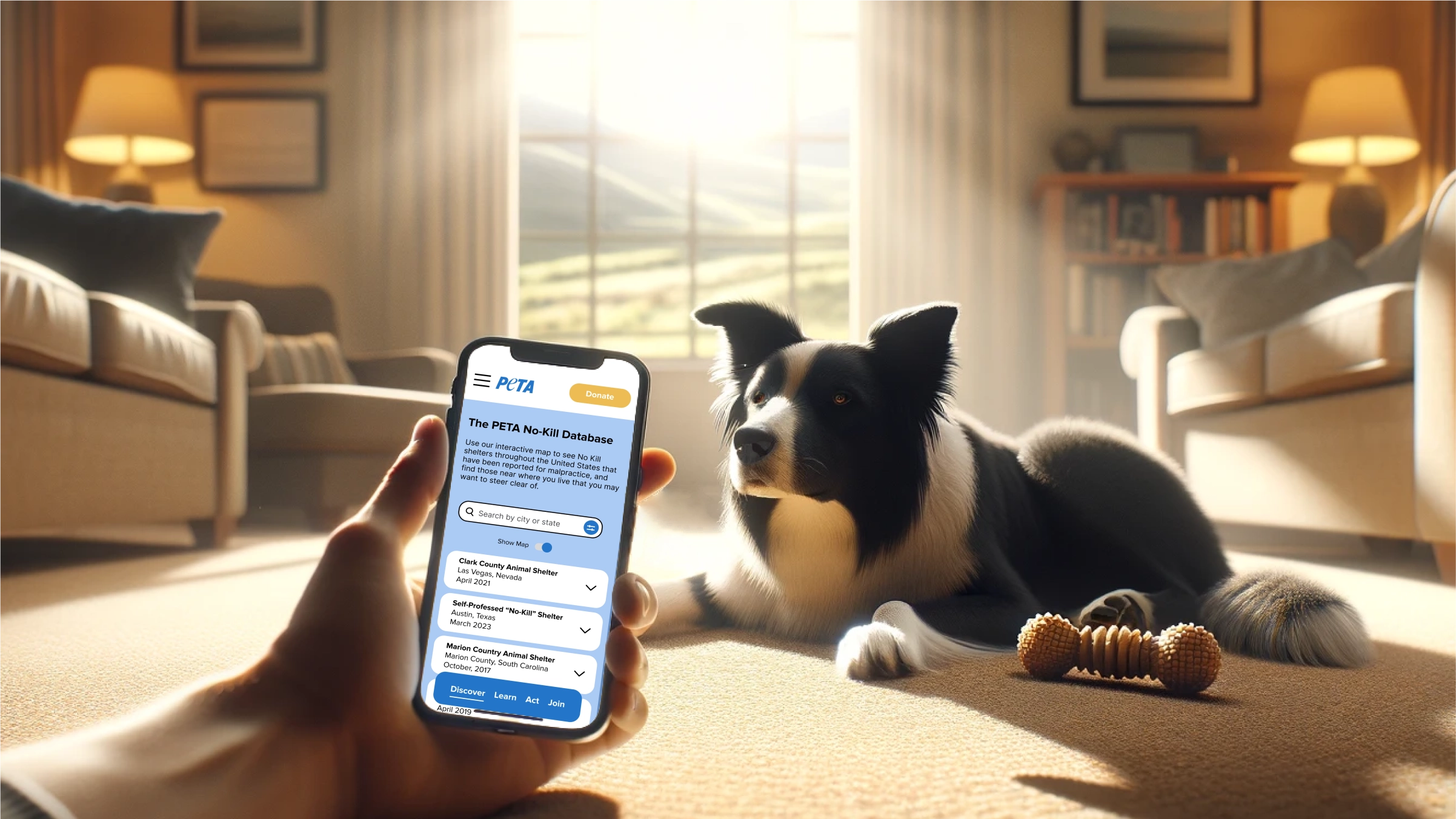

A map-based interface for finding shelters close to home, with easy to access pathways to learn more about the issue and get involved.

One happy client :)

In the early 1990’s, Richard Avanzino had a problem. The animal shelter where he worked was overwhelmed with stray and abandoned pets. Overpopulation was a huge issue, and the shelter, like many others at the time, resorted to euthanasia to keep their numbers down. Avanzino believed that euthanizing was inhumane, so he advocated for a new type of shelter that would never euthanize healthy animals if they had the space to accommodate them.

Today, Avanzino's "no-kill" model has become the standard for animal shelters in the United States, having saved countless animals from unnecessary death. But it's not perfect. While it is effective in cutting down the number of animals that are euthanized, it's created a problem of overcrowding in densely populated areas, leading to a wide range of problems.

No-kill shelters often take in more animals than they have space to accommodate, and with a shortage of resources and adoptions (issues that all shelters have to contend with) they can easily become overcrowded and overwhelmed.

As a result, the animals at the shelter may have to live in cramped and stressful living conditions, with fewer opportunities for enrichment, socialization, and care.

If the shelter isn't able to find homes for their animals, they may become so full they reach capacity. This then causes other healthy animals to be denied admission to the shelter—putting them at risk for neglect, abandonment, or euthanasia elsewhere.

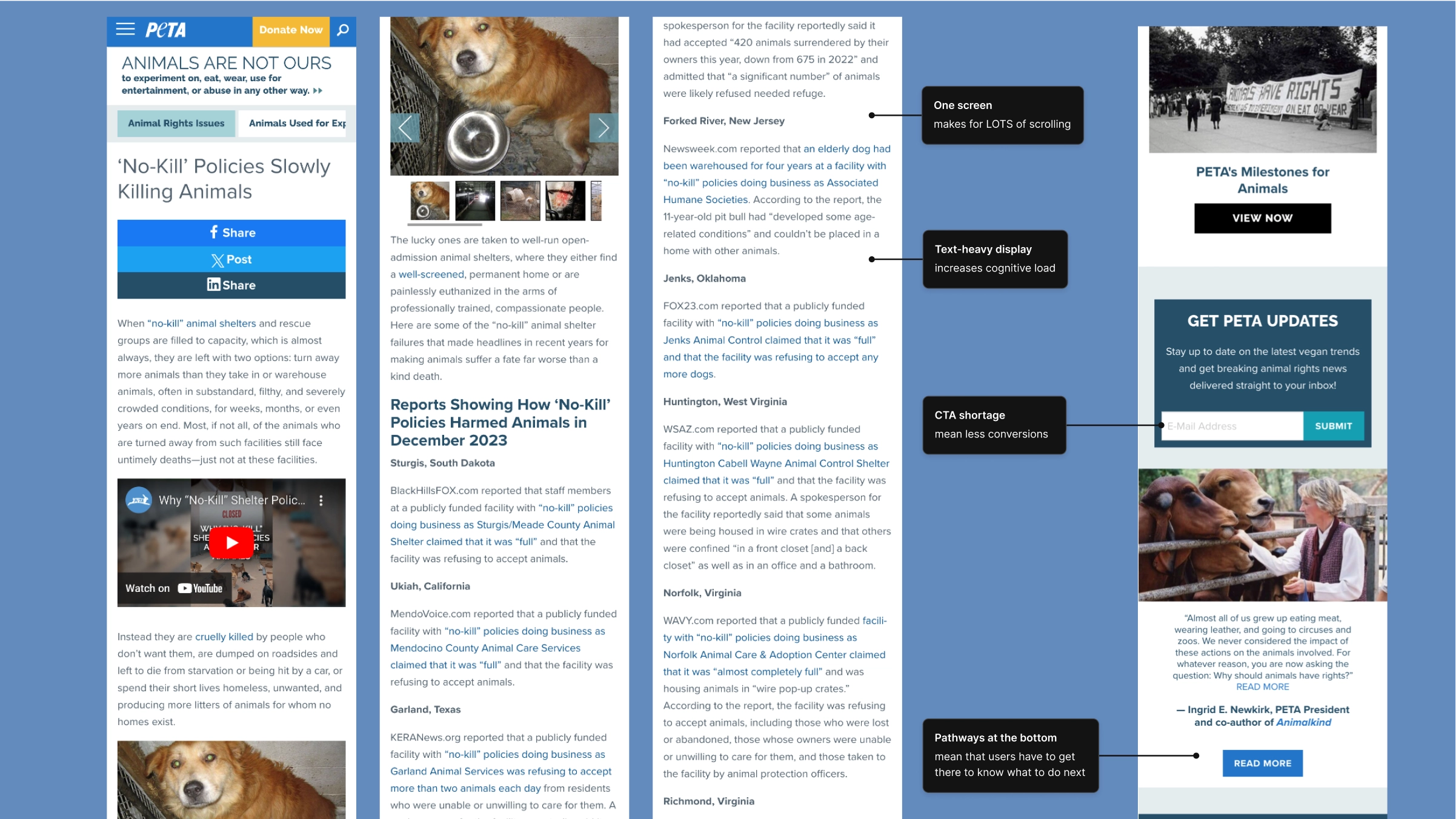

This is the challenge that PETA set out to solve when it created the PETA No-Kill Database—a vast collection of news reports about no-kill shelters that have been accused of following bad practices. With 1,500 reports and 31,000 words, it was the most comprehensive resource of its kind, and one that PETA hoped would encourage readers to learn more about the issue and get involved.

Unfortunately, after years of collecting evidence and tracking the page's performance, PETA acknowledged that no one was using the tool. That's when they decided to bring in some outside help.

PETA partnered with SVC Seattle—a vocational school that offers UX programs where I was then a student—and challenged my team to redesign the page. My team was made up of two UX designers and two UX writers. I led the design of the mobile version of the database over a two-month period, and I collaborated with another designer on the desktop version.

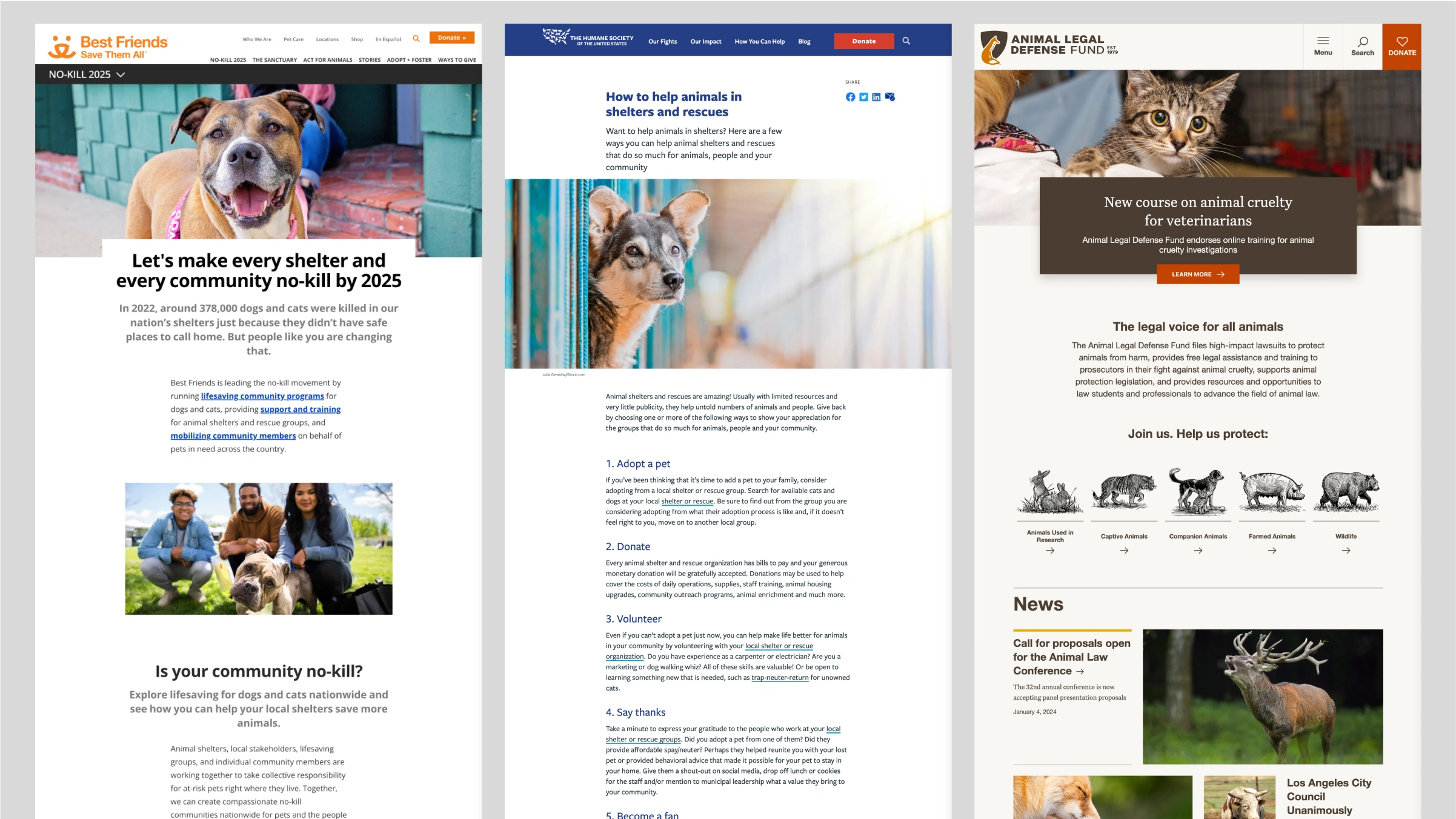

I started the project by conducting a competitor audit, to see how similar organizations were (or weren’t) addressing the topic. To my surprise, many animal-rights organizations championed no-kill as a solution to euthanasia; a sharp contrast to the position that PETA had adopted: that all no-kill shelters were inhumane, and that by encouraging people to avoid them, they could support a more humane approach.

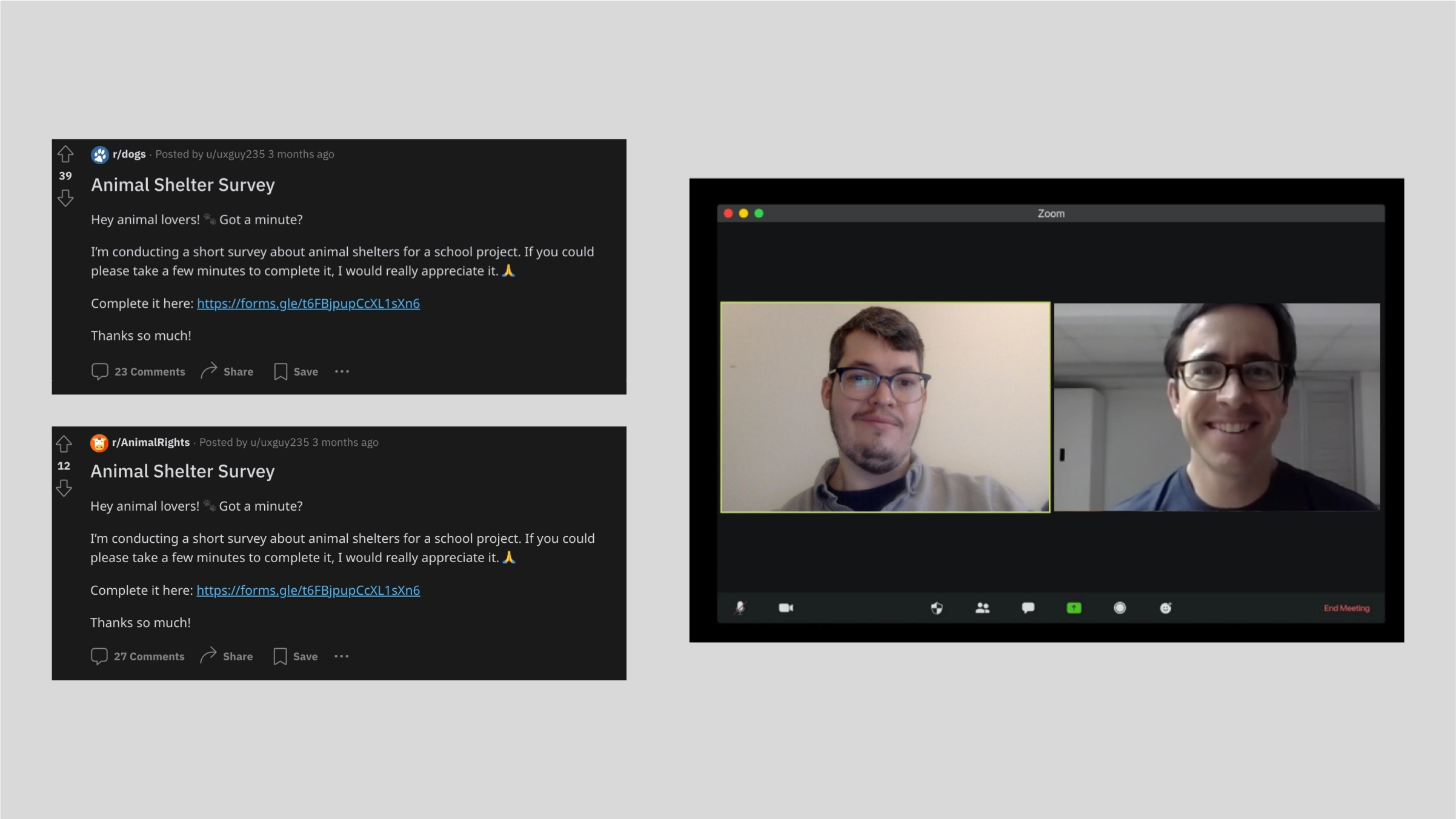

To gain a better understanding of the user perspective on the topic, I conducted several in-person, moderated interviews and shared a survey online, to gather a larger sample of perspectives. I wanted to know how pet owners feel about animal shelters as a whole, what they knew about no-kill policies, and what factors they typically consider when choosing a shelter to surrender a pet.

After analyzing my research findings, I identified several key insights:

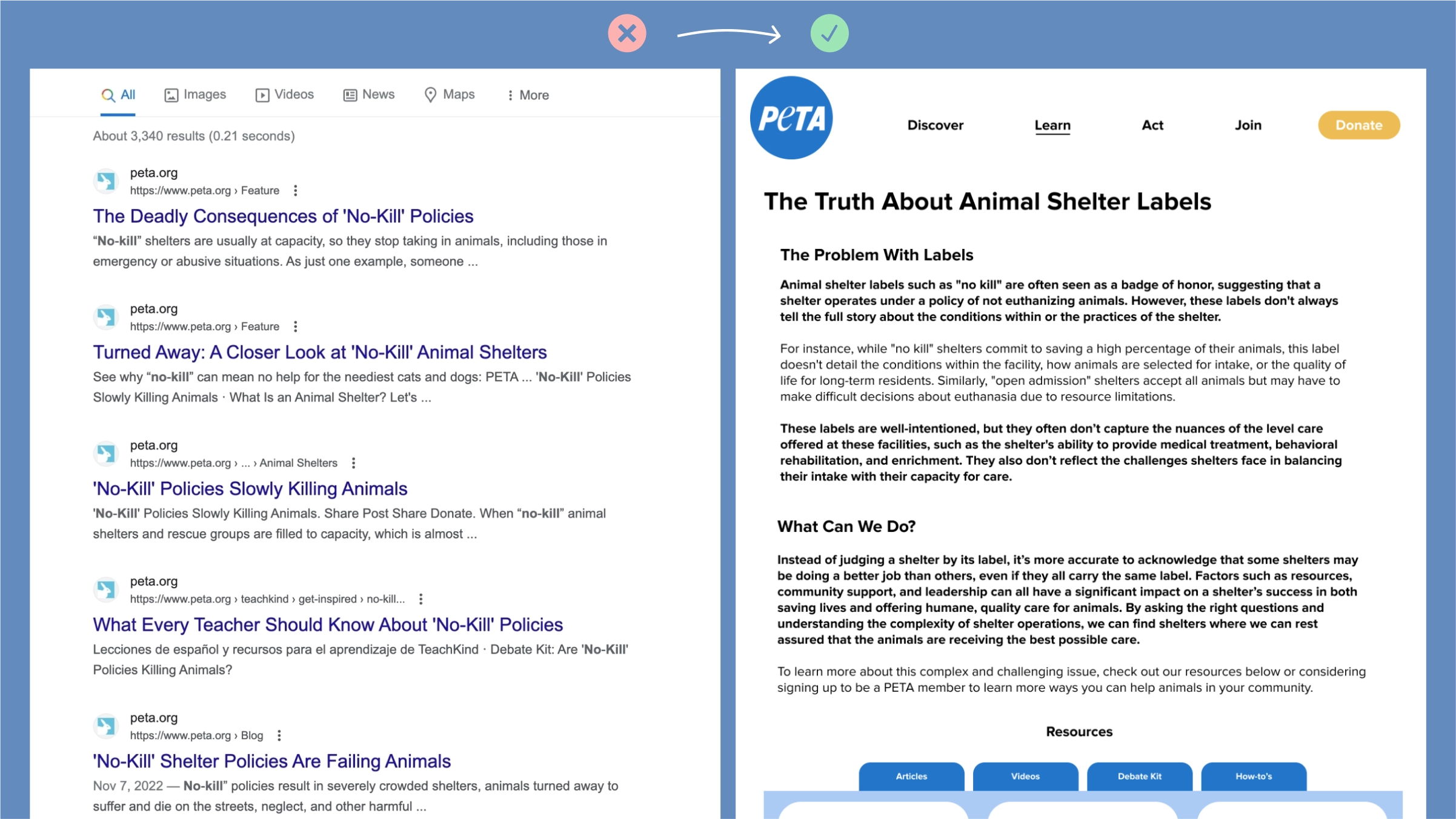

Many people have a general idea of what no-kill is, but unless they’re active in sheltering, are generally unaware that labels like “no-kill” don’t always tell the full story of whether a shelter is humane.

Most people see no-kill shelters as a better alternative to traditional shelters, and will often opt for a no-kill shelter when options are available.

Most people who aren’t active in sheltering don’t actively seek out shelters with specific labels or designations. While people value shelters that provide humane care, they often choose the shelter that is closest to home when they need to surrender a pet.

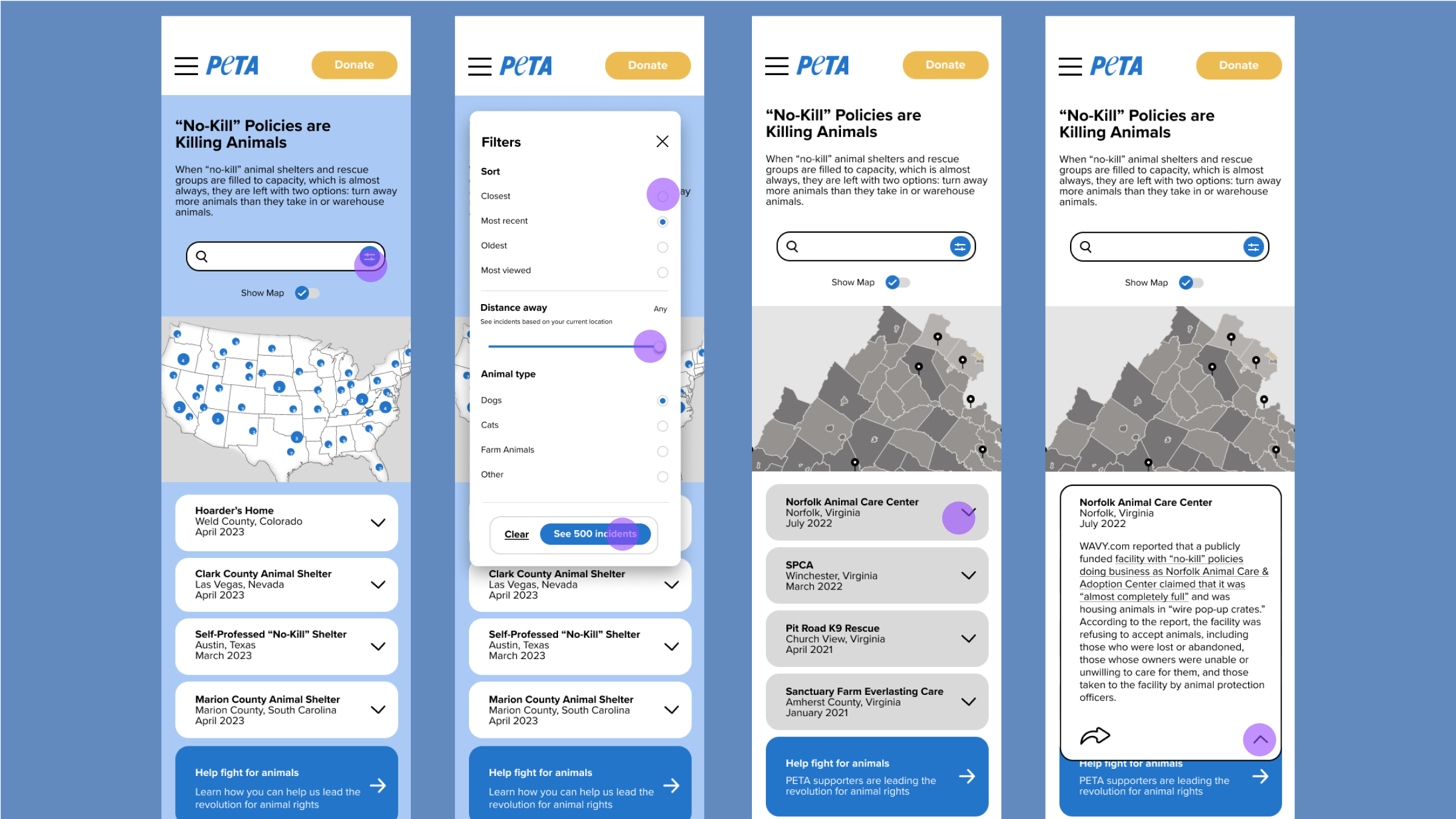

My user interviews also revealed insights about how to make the database itself more useful. When asked what would enable them to use such a tool, many users expressed the need for features like location-based filtering and a more intuitive, less text-heavy display.

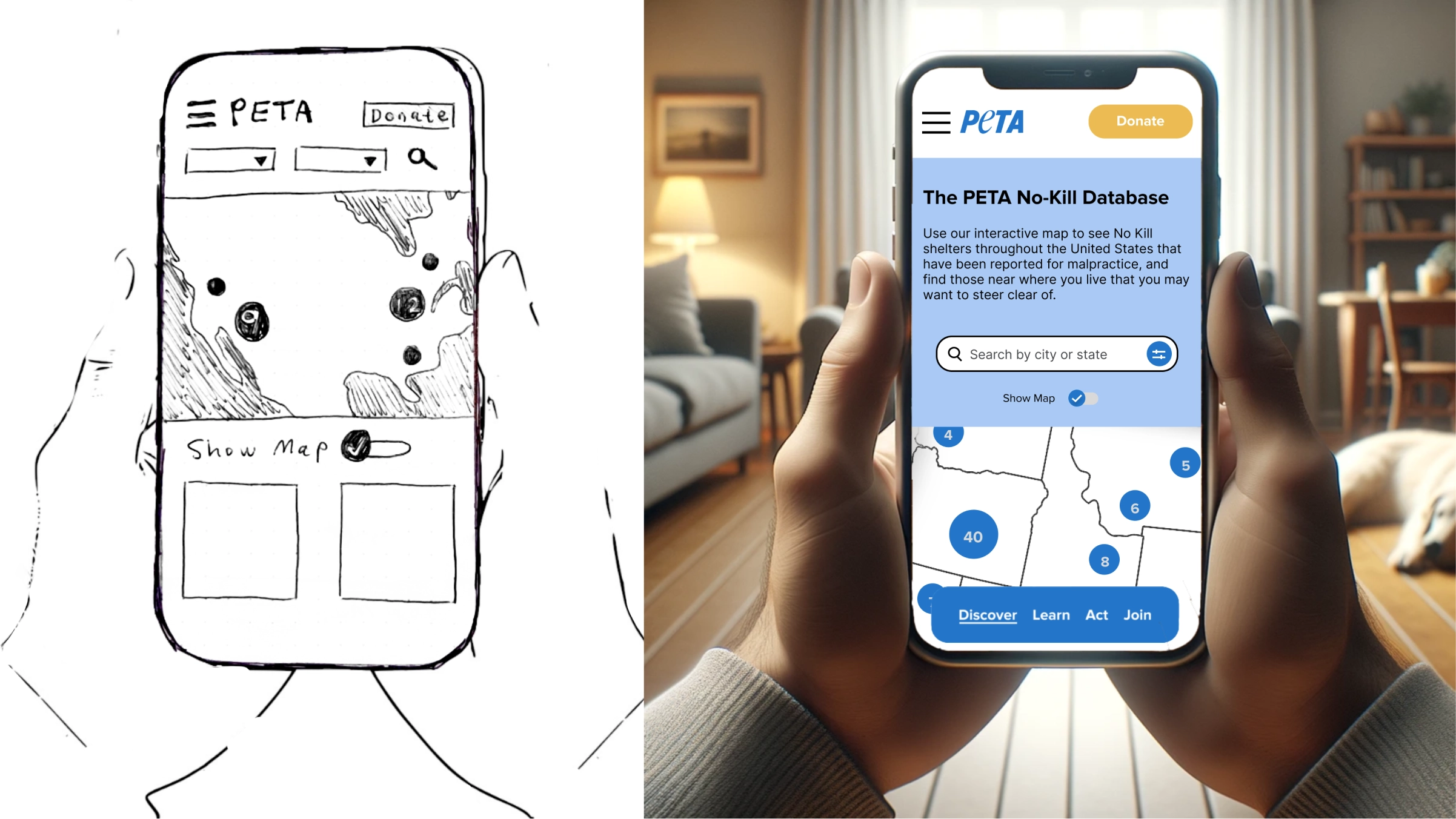

This feedback guided us to design a mobile-friendly, map-based interface for the database, with interactive pins for each news report. This allowed users to filter and sort through incidents that were close to home—suggesting which shelters they may want to avoid in the future.

We also implemented a persistent navigation to provide easy access to the four main sections of the page: one for each of the actions PETA wanted users to take. By breaking up the content into sections, presenting it in bite-sized pieces, and using visual aids and clear calls to action, we made it easier for users to scan the page, find where they wanted to go, and take action.

Finally, based on my research that found that most people (and organizations) support no-kill shelters, we suggested PETA change their narrative about no-kill, in favor of one that highlighted the importance of choosing a reputable shelter when surrendering a pet. By shifting the focus, PETA could continue to push for the humane treatment of animals without vilifying all no-kill shelters and potentially alienating some supporters.

PETA was very receptive to our final design and said that they planned to update the database with our recommendations soon. They appreciated how the new design made the content more accessible, and easier for users to find content that was relevant to them.

This project taught me about the value of doing our due diligence to dig deeper into the user perspective and understand their underlying motivations and attitudes. By taking the initiative to conduct extensive user research and questioning initial assumptions, we were able to create a solution that resonated with PETA's audience and that was more effective in achieving its goals.